In amongst its pages, Chris Parkinson’s newly published Peace Of Wall presents a view of the nation of East Timor that has seldom been contemplated outside of its boundaries – that of one of its strongest social engineering methods; street art.

In honesty, I just binned the editorial introduction for this interview, in which I spieled on about the importance of reflecting on liberty, the ways in which art can enable change, and how humbling it is to see it playing such a healthy role in the foundations of a new nation. After reading back, I realised that the interview already does justice to all those things, and more – and sometimes you just have to let these things speak for themselves.

So, read on, and hopefully, like me, you’ll be thinking about it long after you’ve clicked away … and bought the book, of course …

First things first – what was it took you over to East Timor, and what drew you to spend several years amongst the East Timorese community?

I was at university in WA when I was given a flyer to go up to East Timor as a volunteer to teach English. This was 2001. I went, it changed my life, I finished my degree then committed myself to getting back up there. In 2004 I was able to write myself into a project and stayed. I began working in film and collecting and documenting the country’s rich oral history before shifting to stills photography to capture the graffiti which, I felt, was a contemporary national narrative and astute representation of the country’s recent history. In 2006, when the social and political conflict in the country erupted, I was offered a position with UNDP, working with the 150,000 internally displaced civilians resulting from the conflict. After that, I took a role with UNIFEM, working on women’s political participation and ending violence against women. I guess this focus on oppressed and minority groups, in a context of a much wider oppression in the country as a result of Indonesia’s brutal occupation, really captured my imagination and fostered my intent to remain in the country. It was a fascinating period and I’m hugely humbled by the irony inherent in opportunities revealing themselves to me, in a country defined by subsistence. I’m hopeful that what I may have been able to create and return to the place, in some ways, repays East Timor for the way it has illuminated my life and my understanding of the human condition.

Can you tell me a little about your interest in East Timorese street art, and where that interest came from?

I’d always had an engagement in street art in Australia, but what I found in East Timor was a real story, you know? It was raw, ripe, rough and ready, and the expressions were just fascinating. The images were part reference, part experiential, part catharsis and part just fucking off the hook! Our contemporary western view of street art is defined by a complex system of aesthetics, politics, rebellion, anti-authority, expression and, to some degree, freedom. In East Timor, the idea was completely thrown on its head. Like, through achieving a sense of agency after 400 years of Portuguese colonialism and then 24 years of brutal Indonesian occupation, freedom manifested itself in the most simplistic declarations of self, voice and existence. Graffiti was, and is, the voice of the voiceless. It’s place making, it’s identity forming and it’s a media – in so many various ways – that is accessible by all.

The title of the book, Peace of Wall, has quite a serene mouth-feel to it, how did you coin the phrase?

Ha. I like that. A serene mouth-feel. Nice. I was reading a book by a very funny British journalist called A. A Gill who says in his foreword to his book, Previous Convictions; “There is a necromancy about titles, they are a dark art. When writers meet at literary festivals, in green rooms and in the queue at Oddbins (a British off-licence), what they ask each other nonchalantly, as if they were just being nice, is, ‘What’s it called?’ Not what’s it about? What’s its view? Is writing like gestating the kraken? And they’ll suck on the new title like a borrowed barley sugar.”

So I was pretty conscious about titles and certainly wanted something catchy. But I guess the evolution came from trying to coin the title in Tetun (East Timor’s national language) and I had settled on the title, Didin ba Dame – Walls of Peace. Seemed pretty logical to switch the words, add a pun and, huzzah, a serene mouth-feel title resulted. I guess, as well, it helped navigate the overriding thematic underpinnings of the book.

When did you first think of the idea to capture this work in the book? As a photographer yourself, did this play an essential part in the formation of the idea behind it?

I guess from the outset of the project I was fairly adamant that publishing it was the way to go. I had messed around with ideas of moving it back into an audiovisual piece, then just a straight-up online archive type thing, but I felt pretty driven to conceptualise it all as a story and I guess a book was the logical outlet to reflect the work and the story. That said, some of my favourite photos have hit the cutting-room floor so the online archive process is certainly another outlet I’m looking at to enable a continuity of what’s happening in the country now, as well.

I think that the belief of the work being represented in a book certainly forced me to re-address my techniques of collection, as well. I began, photographically, to add far more context into the images, so that it became more than just a straight up collection of walls, but actually incorporated the lives that inhabited the spaces of where the street art existed. In terms of the interview processes, as well, I had to really re-address what elements of the story that the interviews were going to add, so everything, especially towards the end of my time in East Timor in 2008, became fucking painstaking. There was always something I felt I was missing. But it came good in the end I guess.

There are a multitude of artists within the book, what are some of the stand out examples of the books content?

Well, without trying to generalise it all, everything has a place and everything has an importance. I mean, when you realise the conditions that inform the work, the history that is echoed through the street-art and the perseverance of the country’s quest for peace and harmony, it’s just kind of fucking awe-inspiring that this impetus to create even exists. Certainly the juxtaposition between the proliferation of very harsh political and negative messaging that occurred in 2006, off-set with the very direct peaceful messaging that responded was a fascinating interplay and exchange. I guess my little theory on the presence of ghosts, skulls and skeletons as a result of the country’s history is another element of the book’s contents that appeals to me. So do the gender representations, actually. So yeah, I’m swinging back. It’s all a pretty interesting viewpoint; from anthropological, to historical, to artistic, to communicative appreciations.

The preface for the book was done by Jose Ramos-Horta – can you tell us a little about his involvement, and how it came to be that the President of East Timor wrote a preface for a book celebrating a style of art that’s not always appreciated by politicians?

Yeah how’s that?! A Nobel peace laureate giving ups to a form of expression that some other mug views as vandalism. I can only hope that a few politicians cop on to what Ramos-Horta has to say and wise the fuck up!

In 2006 he supported Arte Moris, the country’s free art school, to paint murals all over the country encouraging peace, unity and harmony. Again, this is something that can’t be under-represented. The walls and surfaces in East Timor are THE way to communicate. Not all people read or write, so the newspapers are a luxury. Many don’t have tv’s or radios. Many can’t afford pens and paper. Many would look at you like you had two heads if you were to try to explain the internet. So, public forums become walls. And public messaging becomes the street-art. And none of our western democracies are above seeing the value in this. They’re just too arrogant to realise its potential. I’d like Ramos-Horta to do a global speaking tour on the subject. He and JR could wax lyrical on how street art has transformed the lives of others. And those weird right-wing anti graffiti fundamentalists could moderate and note take with sharpies on the walls of the forums at which they spoke.

Now that would be a good round table discussion.

There is a strong connection between Australia and East Timor, but what about its connection to the street art scene here in Melbourne and the rest of the country? Are there any definable aspects in that relationship that you drew up when putting the book together?

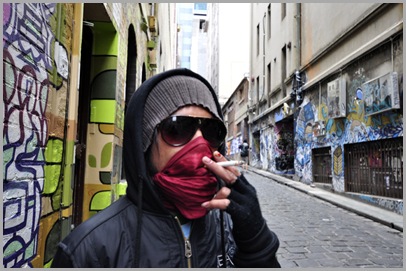

Not really. Just a celebration of the similarity in expression, and a celebration of the difference in that expression. Like the street-art from East Timor isn’t the kind of work you’re going to find in a Melbourne laneway for example. That said, though, the last ten days has been a riot of connectivity of like-minded individuals. We brought three East Timorese artists down for the launch of the book and they painted a mural in Hosier lane (so now I guess you can find a piece of East Timorese street art in a Melbourne laneway) participated in an exhibition of stills from the book at the Until Never gallery, where they painted a mural with a political message about the relationship between Australia and East Timor and the oil and gas, worked with the SIGNAL youth art space and painted a canvas as part of the book launch. So, as an off-shoot of the book, I’ve really tried to establish a connection between the East Timorese scene and the Australian scene.

I’ve been absolutely fucking blown away by the generosity and good-will that has stemmed from this process. Members of the Melbourne street-art scene have been awesome, and I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the following people for their participation and willingness to engage in the project:

Andy Mac at Until Never, HAHA, Vexta, Deb, Monkey, Fiona Hillary and Simon Spain at SIGNAL, Martin Hughes at Affirm Press, Kerry Robinson and Marcos Davidson.

I’m really hopeful that this aspect of the book, the exchange and the connections, will be enduring, and herald a series of new programs that will allow East Timorese artists to return here – in addition to allowing Melbourne artists to venture to East Timor, paint, and teach a cross-section of the country who are hugely inspired to develop their practice.

Several of the artists featured in the book came down for the book launch, how did they find the experience and what do you believe the artists, as well as the community here, have gained from their visit?

Um, I think the lads who came down to Melbourne have returned to East Timor with, and I quote, stars in their eyes. They have been worked very hard, and were fatigued to the point of not being able to speak when they got on the plane last night, but they’ve been blown away by the skills and ethic they experienced whilst here. I had to laugh as they stopped painting their mural in Hosier lane just to watch the Melbourne crew. I can’t say how what they experienced here will materialise back in their lives in East Timor, nor vice-versa for the artists here, but I reckon the solidarity developed is a wonderful foundation to move forwards from.

The idea of the book, and what I’d hope people gleaned from being involved in the lads’ visit, is a new appreciation of East Timor. As Australians, we learn very little about East Timor from the mainstream media. Once the guns are sheathed and the conflict subsides, we get fuck-all really. I just hope that we’ve been able to articulate that, in East Timor, there is far more than meets the eye.

What was the most challenging aspect you faced when putting together the book?

The book was all about connectivity and the cross-pollination of ideas. I had the luxury of time, so really it came down to building trust amongst people and catering to their expectation that they’d be represented properly and honestly. As this was something that took six years to piece together, it all seemed a fairly organic process, so my overall reflection of it would be one of pleasant surprise and gratitude that I’m able to access the means to achieve a dream, you know. That said, though, I think the biggest challenge, on a personal level, has been reconciling the value I see inherent in a publication like this, with the value systems of a generally apathetic and unimaginative Australian public.

In terms of the collection of everything, I certainly had some substantially hairy experiences that involved samurai swords and, on occasions, rocks, but overall, everything really just flowed. I guess I was able to connect with a vast cross-section of communities in the country as I put together the interviews and images for the book, so the scope of learning I underwent was, at times, exhaustive. Doing this book has been one of the most formative experiences of my life, though. I’ve learnt much and I’m hopeful have been able to transfer a bit back in return.

Can you tell us a little about the exhibition that you put on in conjunction with the book launch – it seems a logical thing to do alongside the book, but putting together both book and a show must have been quite a mission?

Yeah, so the lovely Andy Mac jumped on board and hooked us up with the Until Never gallery and allowed an opportunity to fuse the photographic documentation with a very contemporary representation of where East Timor’s street art scene is heading. I think there were about 120 still shots included in the exhibition, and the lads, Alfeo, Etson and Xisto, painted the galleries back wall. Their piece focused on the relationship between East Timor and Australia and the oil and gas, interwoven with a painted representation of East Timor’s traditional textile – the Tais – as well as little references to life in East Timor. There were some traditional houses incorporated into the piece, as well as some UN helicopters and cars. They used a fish-hook, transposed into a question mark, to add more weight and voice to the piece, and we then used this motif around the photographic images as well. It was a collaboration aimed at questioning the relationship and understanding Australian’s have with our near neighbour.

The last week has been quite a blur and doing the gallery event, the book launch, as well as the mural on Saturday, and a day of painting at SIGNAL youth art space, has been taxing yet very rewarding. As I mentioned earlier, none of it could have happened without the help and support of many, and we’ve been very lucky that so much energy was contributed. I reckon, though, I’ll be chilling out for a couple of weeks now!

Where do you believe the East Timorese street art scene is going to go from here, and what do you believe are going to be the biggest challenges they face with their emerging identity, not only as street artists, but as social advocates?

I really think we are just witnessing the beginning of something amazing and poignant. The artists involved in taking the lead, at this point of time, are hugely driven, passionate and inspired. They are always thinking and, with humility, understand their role as advocates for peace and harmony in the country. I was blessed to be able to engage in a very a candid way with the lads while they were here, and they really understand the power of what they are doing in East Timor, and what they experienced in Melbourne. They’re fucking ready to rock, and I reckon the next five years are going to yield some amazing results and collaborations in the country.

As Timor’s identity develops, I think we’ll start seeing a lot more diversity in the forms of expression coming from the country. I mean, in 1999, the place was decimated. In 2002, the United Nations handed over administration. So you’re talking about a country that’s just getting started – and in eight brief years, they have an art scene that is thriving, resilient, relevant and recognised as panacea to conflict. It’s a scene that keeps re-asserting itself as a marker of identity and continues to insinuate positive representations and messages around the country. I mean socially, these artists continue to challenge representations of the country’s history and contemporary culture. The one that resonates from me is the way that, through art, these artists are bringing the role of women back into the social consciousness. Through cultural representations of gender motifs, they are painting women back into a picture that has been exclusively male-centric. The cultural gift that Alfeo, Etson and Xisto left in Hosier lane, for example, is a direct statement on acknowledging the role of women in East Timor’s recent history. So these guys are continuously challenging the norm and offering breadth to the understanding of the social and human condition in the country.

They’ve faced challenges that have been insurmountable over the past five years, and have come out from those challenges stronger and more committed. What more do you throw at a group of people that have experienced genocide, civil conflict, refugees in their schools, and threats to their pursuit of peace?

I’m rubbing my hands with glee at the thought of how these cats are going to illuminate the lives of their fellow country(wo)men, and further paint themselves into the global picture – so bring it on!

You can buy Peace of Wall online from Affirm Press, or at good bookstores. Also check out Chris’s Parkinsons blog for info, photos, dialogues, East Timorese street art, and more.

1 comment

1 Comment

Virginia Travers

15 years agoHi I am a 58n year old mother from Marin County CA

REPLYI really enjoyed reading about your work in East Timor. I am an artist and a film producer with a feature film about East Timor in development. I hope to travel there in November if not before. Keep doing what you do it’s important, It’s the persistance and determination of the seemingly mortal dreamer who steadfastly holds a new thought in mind, either of the creation or of it’s inevitable success,even while the rest of the world is content dreaming their fathers dreams. TUT