I can pinpoint where I met E.L.K. to the exact moment, and I can remember quite clearly, exactly, what was said and what happened. In fact, I wrote about it, so even if my memory had of, by chance, been a little hazy its all there.

It was, truth be told, something of a “moment” for me. On the one hand, that moment was the beginning of an entirely unexpected friendship with a man whose friendship I both respect and treasure, and on the other it was one of those moments that a writer looks back on and goes “I was there!” with some amount of pride (intermingled with a slight fraction of awe) – because, sitting here a year and a half later, at that time I had very little idea of where E.L.K. would be with today.

Neither, of course, did he.

Some of his words to me, back in the park where we first met, echoed in my mind as we sat down at The Vic last week, drinks in hand.

“If you can make a living, successfully,” doing what you love doing and doing what you’re good at,” he remarked “ … it’s the dream!”

In the past year and a half, a part of this dream has, in truth, come true for E.L.K. His love for art, his passion and dedication over the years have paid off in many ways, and he now spends his “working hours” creating his art – but even being granted a partial aspect of his artistic dream hasn’t come without its own trials.

“I thought it would take a lot longer to get where I am,” he remarks, humbly as always, when I catch up with him. “I thought, ten years maybe, realistically. But it really has been a big couple of years.”

“I do feel tired,” he laughs. “Not I need a nap tired – I’m fucking drained!”

The fact that he can laugh about it all, however, marks that he has also taken it in his stride – because it really has been a big fucking year for E.L.K.

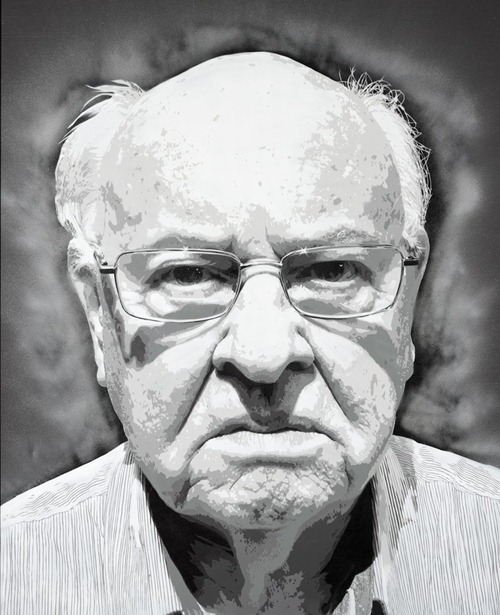

After moving to Melbourne from Canberra, it seemed as if it was all systems go right from the very start. Although now residing in Richmond at Paradise Hills, E.L.K. did a short stint at Blender studios, where he immediately got to work on a new portrait piece of the much loved and notable Fr Bob Maguire.

When he first submitted Fr Bobs portrait to the Archibald prize, E.L.K. was less than certain as to how it would be received, this was, after all, one of the biggest contemporary art prizes in Australia. That it was selected to take part in the actual competition itself was not only a major win for street derived art in general, but it was a phenomenal boost for the career of an artist who had literally worked his ass off – it was another win for the acknowledgement that street derived art has a place in Australian contemporary art, and E.L.K. was at the forefront of it all.

“Its been a really big wave – a huge wave,” he explains when we start talking about his reflects on the Archibald “experience”.

“Not so much the Archibald itself, but the buzz surrounding it, the media surrounding it. Nothing prepares you for it. It’s what we all want – but when it actually happens, fuck, you can’t go back from it. Actually ‘making it’ can be pretty scary – but once you face it … well, not so much. ”

Beyond the media, the promotion and the entire “mainstream” rigmarole behind the Archibald, being a part of the whole process and event also gave E.L.K. something that he believed he was missing, something worth more in his mind than all the rest.

“It gave me more confidence,” he confided. “Which really was something I was lacking, within myself and with my art.” He sits back and takes a drink before putting on a wry grin, “Yeah, it was definitely an awesome ride.

“I felt like I was almost tapping into the zeitgeist,” he continued, talking about the entire experience. “The subject, the timing an the award, and it was just the right time. I think the Art Gallery of NSW was looking to introduce street art into the award, but they just hadn’t quite had the right piece. So, the planets aligned and it just … I felt like there was something a lot more spiritual going on behind the scenes, which is funny, coming from an atheist, but there was more to it I felt.”

E.L.K.s Archibald piece none withstanding, as a hardcore atheist, there was more than one “spiritual connection” that came from the experience – the other being the formation of a friendship with his subject.

“I’ve become quite close with Fr Bob,” he says, smiling. “He’s a great guy. I’m like a 33 year old, and he’s much older … but we’re quite the same – kindred souls. He just says it how it is, and that’s something I’ve always done, and said. I may not always be right, but that’s my perception. With Fr Bob there’s no bullshit, and I respect that. It’s just nice to come across. Particularly in regards to the art world, you come across a lot of bullshit, so it’s nice to have a bit of truth.”

“We do talk quite regularly. I had a call from him last week and he said ‘what’s this about my face popping up all over town” he laughs, obviously making mention of the many Fr Bob stickers that have surreptitiously been springing up around Melbourne of late “… I kinda said, well, I can have a chat to them if you want, and I can see if they’ll stop doing it!”

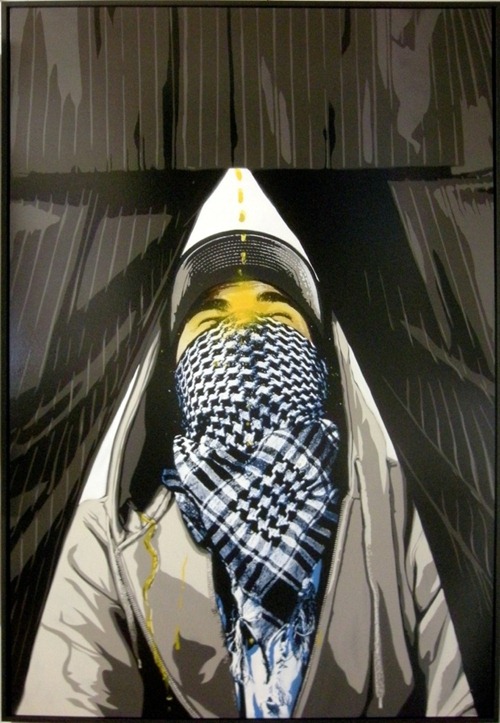

Not only did E.L.K. form a bond with Fr Bob over the work, but it also lead him in a new direction with his work. Whereby previously, his work focused heavily on the portrayal of issues and other societal concerns, he found himself recently changing direction towards a more classically orientated bent – portraiture.

“I’ve actually concentrated a lot more on portraiture and less on the street sort of social commentary work that I’ve done,” he explained. “I think id like to establish myself more as a portrait artist than a stencil artist, to be honest.”

“The whole process of selecting a subject, meeting the subject and making the art and capturing that subject is great. Also, for me, and mainly, just the whole unveiling of the piece to the subject can be really touching.”

As a man who has for time now been acknowledged as a master of his chosen technique, with stencils comprising up to seventy different layers of high degrees of detail, as well as an individual who has tackled subjects including war, religion, consumption and greed, it is this human touch to his new works in portraiture that have him flowing with exuberance.

“I don’t know what it is about it – its all, imagery creation,” he says, laconically, “but it really has nothing to do with technique anymore. It’s all about subject and content. I have the technique down pat – but getting the right image, and making it all work, that’s the hard part.”

Thus, his upcoming solo show at Metro Gallery, “Not With It”, is something of an explorative body of work for E.L.K.. Of course, within the show are several of his older themed pieces of social commentary, older themed work, but the body of the show, and the epic mainstay for a certainty, is in the portraiture that he will be displaying. Having been through a portion of the maelstrom of “success” and not gone down with the ship in the process, it seems that this has had nothing but a positive effect.

“It was really about pushing myself, in many ways,” he explains, “and to not worry about it too much. Just man-ing up and getting into it – which is what I did – but it wasn’t easy.”

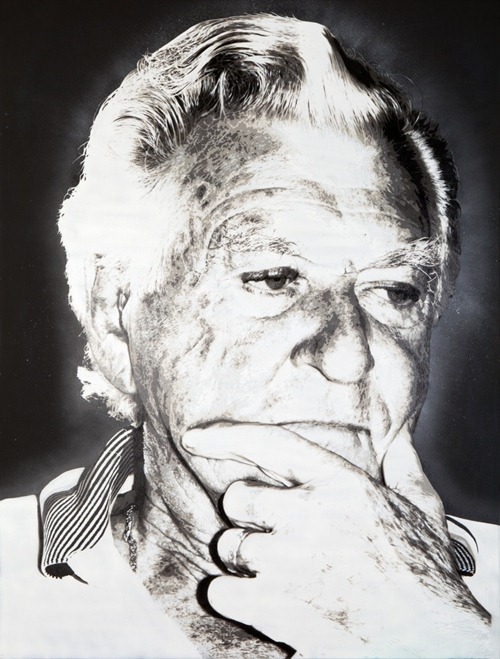

In fact, when we caught up at Paradise Hills that night, before our sojourn down to the pub on Victoria Street, E.L.K. had only just finished a portrait of aboriginal actor Jack Charles. The work is massive, one of the largest and most intricate pieces that I have ever seen him produce. The shades and tones of the work left me breathless, and as he pulls up a photo of it I can’t help but think that for all the “success” that he has had thus far, that this is only the beginning.

“It took me three weeks to do that piece,” he says, almost belying the effort behind it. “It was all about pushing things further … I can’t do what I used to do. I can’t sit down and cut for a hundred hours … it’s really good, but I’m tired.”

“It’s a really good kind of tired, though.”

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *